Expat Brat #5

(A note from Crash. Thanks to Charlotte Agell for providing such a wondrous look at her life and those she met along the way. This is her final contribution to The Crash Report, but she’s continuing the journey over on her own Substack. Follow her via Charlotte Agell . Scroll down for links to her earlier gifts to The Crash Report . )

It is January of 1971 when we leave Sweden for Hong Kong. My sister and I wear scratchy woolen kilts, white cardigans and matching white knee socks. (It is important to look glamorous on an airplane.) I wear a sullen expression. My brother wears a jacket and tie. He carries a small briefcase, as if Volvo were dispatching the world’s most debonair 4-year-old to set up factories in China and Indonesia. Really it is my father who has this new job. I don’t want to leave my sixth grade class in Stockholm. I was making friends. I was just getting used to being back in Sweden.

I have been here before, though. Leaving one world for another. And I know what is going on, which is that I do not know what is going on.

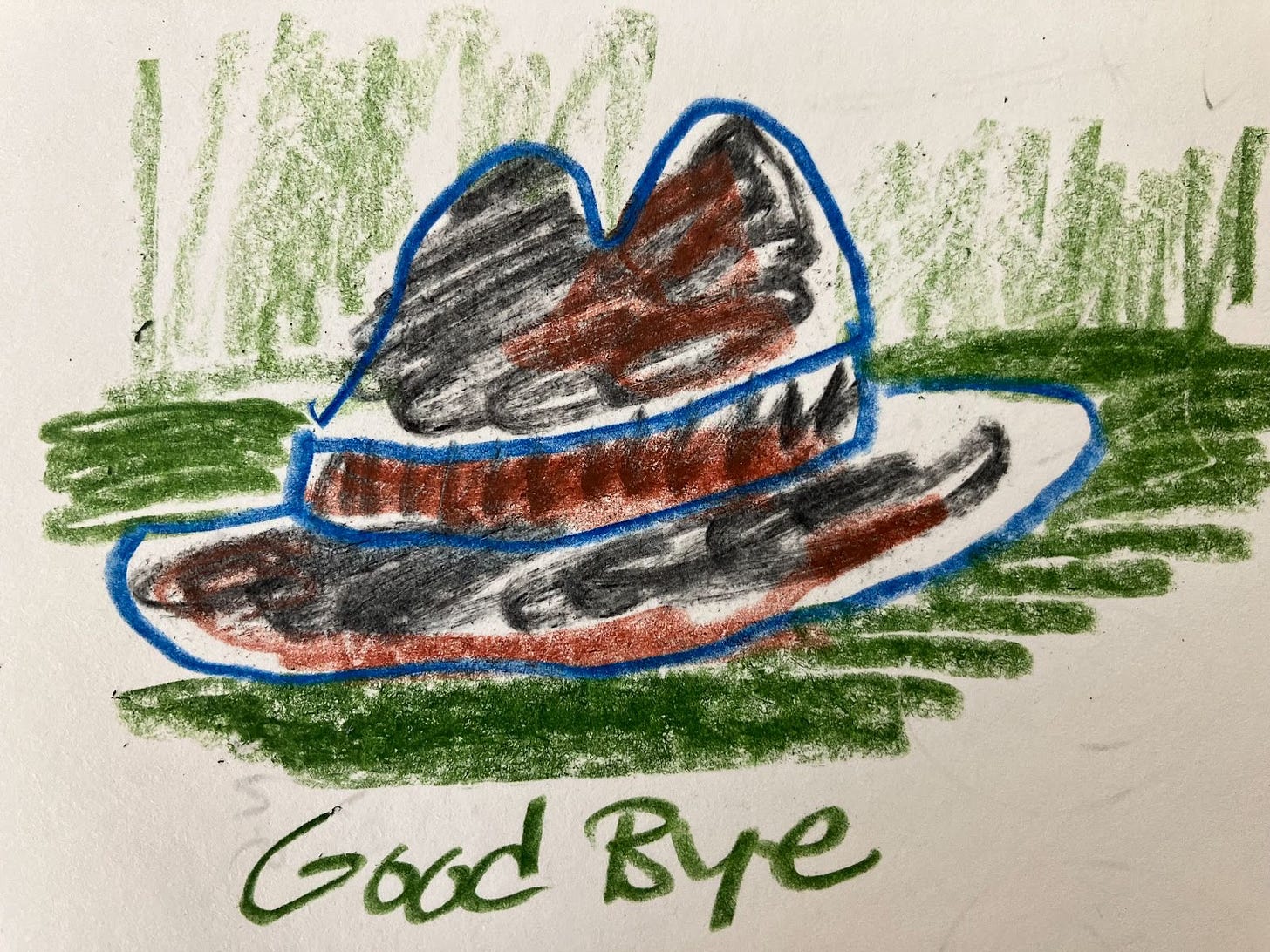

We hopscotch across the planet. (Fuel tanks are smaller back then.) By the time we land in Bangkok, my woolen kilt feels especially wrong. It’s so hot. The air is humid and somehow smells both like diesel and strong, strange flowers. My father forgets his hat on the sticky seat of the airport minibus. After that, I don’t see such a hat again until the Annie Hall movie comes out and I wear one myself.

Without the hat, my father becomes someone else. Someone launching himself into a new life that could take him - and us - anywhere.

We reach the Repulse Bay Hotel, named after a British warship, in the middle of the night. The next morning, I go outside to look around. The hotel sprawls like something I will later read about in a Somerset Maugham novel - all verandahs and wings - as if there is no space it cannot take up. (The room I share with my sister is tall enough to play badminton in, and we do. The shuttlecock gets stuck on the ceiling fan. We don’t see much of my father. He is continuing the regime he started while the rest of us were back in Sweden: Figuring out car transports, setting up factories, and sleeping with his twenty-something year old British secretary, she of the mod haircut, painted eyes and sweet lips. )

Outside, there is a tortoise. He paddles around a stinky cement pond, a red banner on his shell. He is 150 years old, someone tells me. The banner on his back says LUCKY. He does not seem that lucky to me.

In Sweden, my sister and I had kept turtles the size of coins in the downstairs bathroom, in the bidet. We fed them chunks of raw meat and watched them paddle furiously around in their miniature porcelain world. My mother must have counted on them not lasting too long, knowing, as she did, that we wouldn’t be staying long at home in Sweden. They did die. We quickly forgot them. But now I was thinking about turtles again. Turtles - those world bearers, carrying the whole of their EVERYthing on their backs. They were lucky. They always had their own house with them.

The sprawling hotel (Empire takes up room!) was surrounded by flowers. Their scent was a new kind of perfume. But I was skeptical of EVERYthing and didn’t feel like liking much of anything….

During the four and a half hotel months we spend in the hotel, I become Eloise. Eloise the children’s book hero. Eloise of the NYC Plaza Fame (she had a turtle, too - Skipperdee!) Eloise is very entitled and annoying. This is not who I am at the Island School, where I am the youngest and possibly the most afraid. (Why have my parents put me in first form in a British School instead of in the sixth grade I was halfway through?) The first day there, the bosomy 13-year old elected to show me around the school merely asks me in the hallway, “So, you wanna smoke in a loo?” I’ve read enough British books to know what she means about a loo, which is also apparently called the bog. “No, thank you,” I shake my head. She goes into the lavatory, has her ciggie, and the tour is over. She’s clearly a teenager. I am clearly a child. The Peter Pan in me doesn’t even want to live in her country.

To get to school I take a bus. Every morning, I walk down the hotel steps in my very short school uniform. (It is the early 70s after all.) I am eleven. Every afternoon when I return, I have to dodge a phalanx of male Japanese tourists who grab me and have me pose for photos with them, arms draped around my neck, smiling and laughing. I don’t understand why in the least.

Guests come and go from that hotel, but we stay. It’s as if we are on permanent holiday while simultaneously conducting our real lives. My father goes to his office. My sister and I go to school. I don’t really know what my mother and my little brother do all day. It doesn’t feel real. It doesn’t feel like Home will ever happen again. I start to wish I were a turtle, with my house on my very own back.

One day, my sister and I are so bored that we tuck Karl under one of the low rattan tables in the bar. It is midday. There are no patrons. Karl is delighted to play loud, scary tiger under there. The waiters do not stop us. Our Cantonese is non-existent; their English is not that great either. The waiters laugh behind their hands, which is the way Chinese women usually laugh, unless they are in the market arguing about prices, in which case they are very loud. The waiters are probably laughing because they don’t know what to do with such naughty children, children who should know better. (I know I should know better but I can’t help myself.)

Along comes a paying customer, a fancy British couple or perhaps they are Swiss. (I am getting quite good at telling, even before people start talking.) My sister and I sneak behind a dusty velvet curtain, leaving the scary tiger in his fancy cage. It takes a moment for the couple, intent on each other and on ordering drinks, to notice Karl. He is prowling around, staring at them, occasionally extending a paw, claws out. His roar is a low murmur, almost a purr.

The cocktail drinkers do not laugh. They gesture angrily to a waiter who releases our brother, who then crawls over to us, still in tiger character. We run away laughing, and it is funny but not that funny. I know better. I am the eldest after all.

Most days, we eat supper upstairs in our two rooms. I order meat sauce on rice, over and over again. One of the times we eat supper in the formal dining room, we leave my brother asleep upstairs, as if we were merely downstairs in our own house. When the wait staff, in their white coats and caps, come in bearing a little boy on a silver tray, my mother nearly faints. She believes for one small moment, with open mouth sincerity, that this is my brother and that he is…dead. He has been brought to her on a gurney. She has left him alone and he has died.

The other diners do not notice. This is because it is not Karl. It is actually a lifesize sculpture of a boy, made entirely of butter. The butter boy is leaning back amongst his bed of grapes, looking as mischievous as a putti in one of those Renaissance paintings. My mother rushes up to check on Karl. He is still asleep. She comes back.

The rest of us have some of the butter boy, on white toast. Why not?

After four and a half months in that hotel, we move out to Turtle Cove Villas, into expat housing. It is a part of Hong Kong that manages, at the time, to be remote. The little cove at the foot of our mountain is the turtle’s head; its body merges with the vast South China Sea. Turtles seem to be following me. They want me to be slow and steady, perhaps, but I just want to pull my head into my shell and think.

Charlotte came to Maine from Sweden, via Hong Kong, for a liberal arts education and the 70s rock n' roll. She's a lifelong public school teacher and the author/illustrator of many books for children and young adults. She believes that artists are emotional first responders and that art gives you questions, not answers. Which is why art is so dangerous and so necessary.

Note: Charlotte Agell has been very glad to share some of her Expat Brat memories here on The Crash Report. Thank you for reading! She is mulling what to do next.

Charlotte, always find your mini-memoirs so vivid and offering. ever more glimpses into your fascinating back story. And LOVE those photos. You and Anna look the same. Those knee high white socks, and woolen kilts brought back my own memories. I marvel at how vivid your snippets are and detailed... not sure how you do it but feel you are a true time traveler.